Making UX research accessible

UX research repositories are still a rather new phenomenon. What constitutes a good repository is by no means defined and depends on your goals and organization. In addition, new concepts are forming and learnings are being made constantly.

This article explains three fundamental design decisions we faced when extending our user research software tool Condens to also act as a research repository.

- Same tool for data analysis & archiving vs. separate tools

- Curated results vs. access to all data

- Reports vs. atomic research

You will likely be confronted with the same decisions if you are setting up a repository in your organization. I hope the article helps to inform your decision.

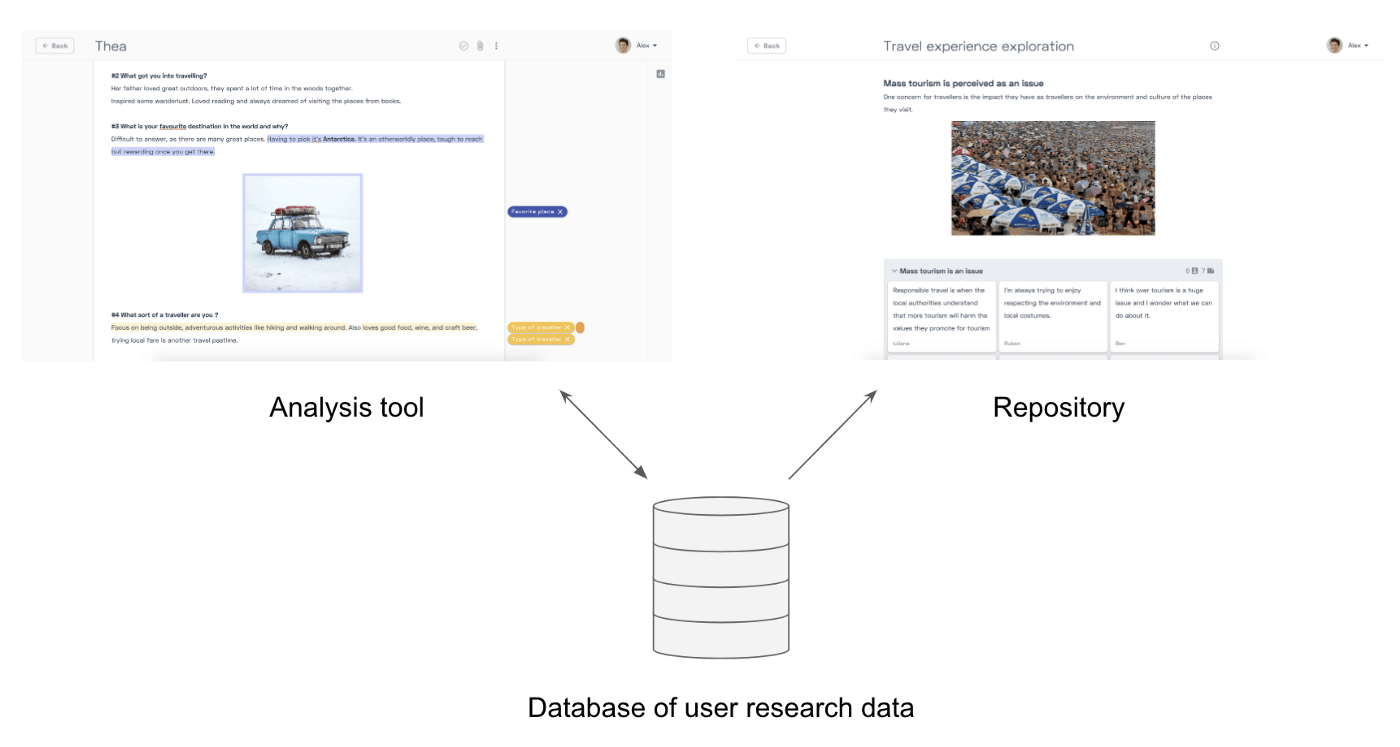

1. Same tool for data analysis & archiving vs. separate tools

Challenge

User research is still a rather new function in organizations. For lack of better alternatives, researchers either had to revert to tools from academia or use general-purpose tools to support their work. For note taking and synthesis, Google Docs, spreadsheets or good old sticky notes are the typical tools of choice. For archiving, data is moved to shared folders or company wikis like Confluence.

With the practice of UX research growing, specialized tools for both data analysis and archiving emerged. It’s now the first time that we can re-define the boundaries of these research-supporting tools.

One important question that follows is: Should data analysis and archiving be handled in the same tool? Or should they be separate? You’ll see that this has significant consequences on how research is archived and re-used.

Consideration

Before writing the first line of code for Condens, we interviewed UX researchers around the world. Research on researchers if you want. Thereby we identified a fundamental misalignment of incentives regarding archiving: As a researcher you have to invest additional time and effort now (to document & store findings properly) such that you or someone else potentially has a benefit in the future (can find them again easily if needed). Concretely the additional effort for archiving includes these steps:

- Gather all data (usually from multiple tools) and move it to the archive

- Organize the data by some logic (e.g. raw data, analysis, findings)

- Add context for searchability (time of study, topics, involved researchers)

Given the significant additional effort, an uncertain future benefit and a rather boring task, not archiving properly often wins — understandably.

Our research showed that the effort for archiving is largely due to separate tools for analysis and repository. This separation acts as a barrier as it requires data from the analysis tools to be adapted for the repository.

Integrating the two tools into one would eliminate the first two steps of the list above — gathering and organizing data — as they are inherently taken care of by using the analysis tool. Also adding context can partially be done automatically by the analysis tool, for example by adding time of study and involved researchers. This leaves minimal effort to add further context. Read more about how repositories can streamline the research process.

Keeping effort for archiving in mind, integrating the two tools into one just makes sense.

Now here is the counterargument:

Considering the users of research repositories, we differentiate between two groups:

1)People who do research (PwDR; thanks

Kate Towsey for inventing this abbreviation) and 2)People who consume research (as this can be anyone in the organization, let’s

call them stakeholders).

While PwDR both conduct and consume research, stakeholders exclusively consume it. These

two groups have different requirements which are difficult to address in the same tool.

Here is an example: When jointly working on a research project it can be very helpful to see what others are doing in real time—for example during note taking or structuring data. However, it’s uncomfortable if the progress of a project is visible to all stakeholders in real time, as it reveals unfinished ideas that may change. Research can be a messy process and we believe PwDR need a safe space to develop insights without the fear of possibly being observed.

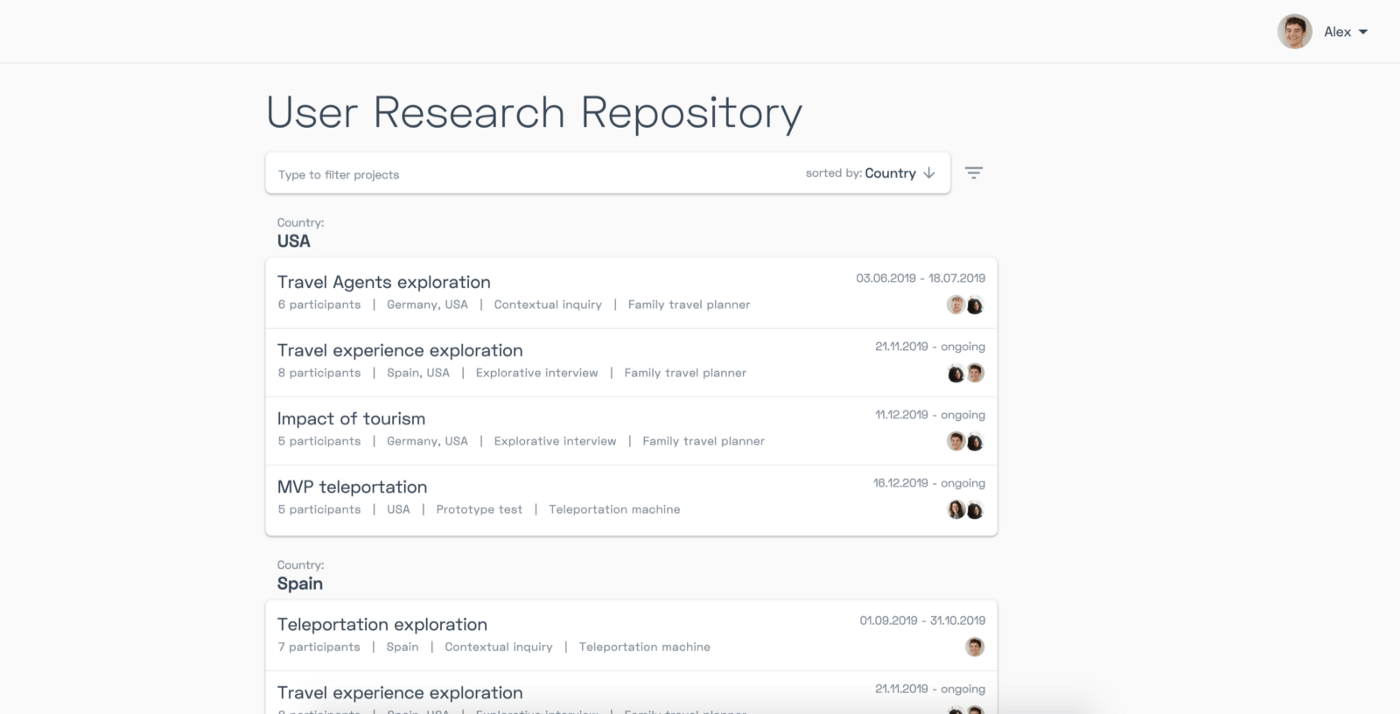

What’s the solution to this contradiction? How to balance the need for integration and separation? At Condens, we aimed to do both and get the best of each world. The tool for analysis and the repository have the same data basis. That ensures that making data available in the repository is minimal effort, literally a click of a button. At the same time, there are two separate interfaces: One for PwDR and one for stakeholders. The interface for stakeholders is read-only to prevent any unintended changes and only shows relevant functionality for this user group.

Drawbacks

The downside of this approach is that it adds another tool for stakeholders compared to your company-wide wiki that everyone already has access to. Some organizations don’t even allow a separate archive for user research and require you to use the company wiki.

Also, there is a decision to be made about who in the organization will have access to the analysis tool and who will be a stakeholder with access to the repositry.

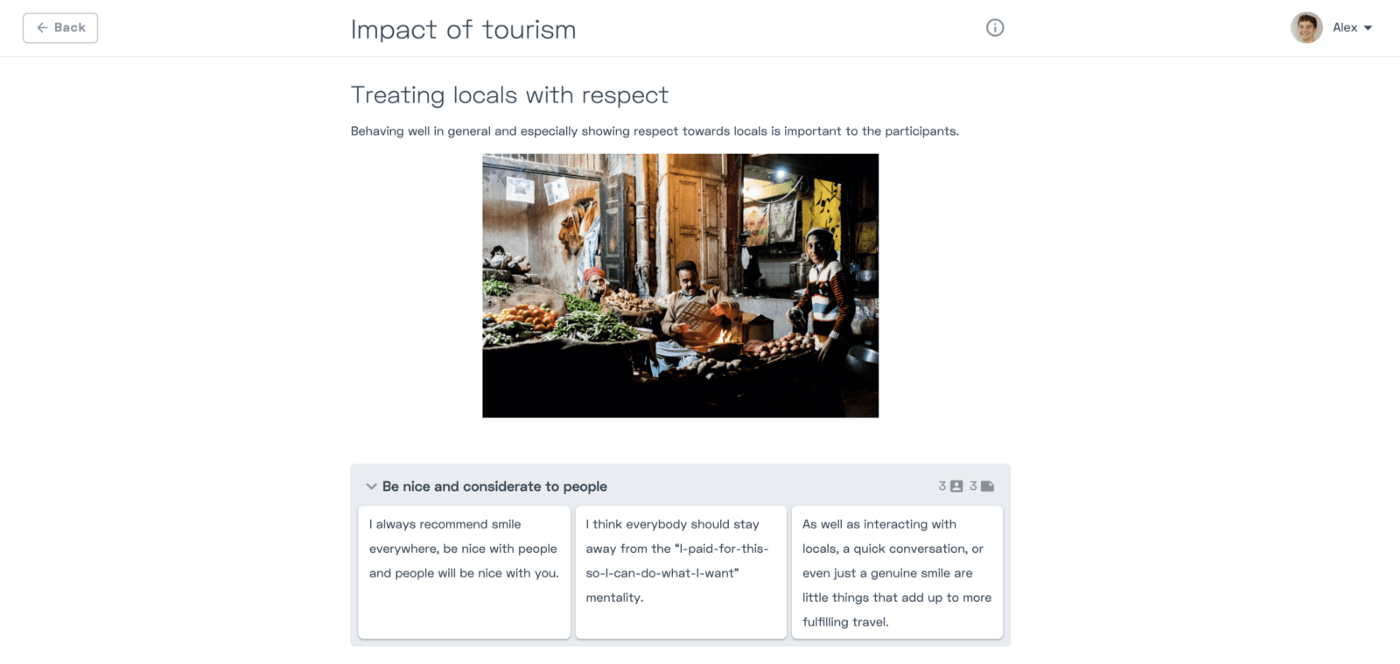

2. Curated results vs. access to all data

Challenge

The next question concerns what part of the research data should be accessible. It seems reasonable to reveal all data to stakeholders. Full transparency about data sources can increase trust and acceptance among the audience. However, user research data is often highly sensitive and demands careful handling. So should stakeholders have access to everything including transcripts, recordings and information about participants? Or should their access be restricted to research findings only?

Consideration

We decided against showing all data in the repository and in favor of giving PwDR the ability to curate what stakeholders can see. In our case this includes findings as well as selected evidence and participant information.

Here are three aspects we considered:

- We believe data privacy to be very imporant, especially in the context of user research. PwDR have the responsibility to handle personal data with care. Therefor we designed Condens to help protect the data of research participants, e.g. by letting PwDR decide whether personal information of participants are published to the repository.

- Making all data available can easily overwhelm an audience and distract from the important aspects. Even more so if that audience has limited time. Just like any other information signals, research findings have to fight for the attention of the audience. It’s more effective to steer the stakeholders’ attention to a few carefully selected key findings.

- Giving stakeholders access to all research data also bears the danger of individual participant statements being taken out of context. Data might be used in wrong ways resulting in misleading conclusions. I’m not assuming colleagues have bad intentions – but there is a reason why conducting research requires proper training especially in detecting and avoiding bias. We believe curation is one of the main skills of researchers, i.e. integrating various data points to form reliable conclusions and recommendations.

3. Reports vs. atomic research

Challenge

The traditional way to store research findings is as reports. Over time, reports turned from dusty text documents, into media-rich presentations conveying the key-findings of a study.

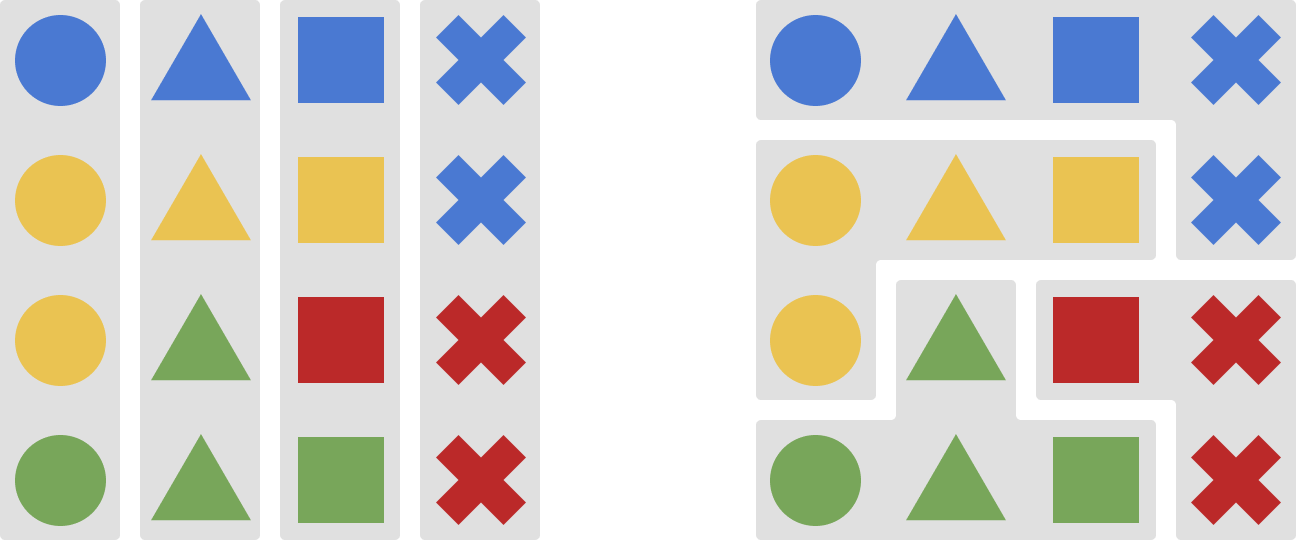

Around 2017 the concept of atomic research came up. The main idea is to store research in digestible chunks or “nuggets” of findings. In simple terms, it’s a different view on the same data. Reports organize data based on where it comes from, nuggets allow to organize it based on what it’s about. In the image below, consider the shapes to be findings from research. Same shape means it originates from the same project while same color means it belongs to the same topic.

So the question is: How should data in the repository be organized?

Consideration

In Condens, past research is accessible in the context of the research project. We decided to not make findings available to stakeholders in form of nuggets and here is why:

- User Research doesn’t produce absolute truths. Context is crucial when interpreting and re-using research results. It takes a researcher’s expertise to put findings into perspective and explain under what circumstances learnings are valid. While atomic research doesn’t ignore context, it tends to put the finding in the spotlight and context into the background. That’s why we see the risk that important decisions might be based on misinterpreted or invalid nuggets.

- Summarizing findings to answer the research questions is something that PwDR anyways do when conducting a study. These findings can be taken as they are and made available in the repository. However, it requires additional effort to organize nuggets and make them usable for others. At the end of each study, PwDR would have to match nuggets to related topics — no matter if they are relevant for the original research question or not. This overhead easily becomes a hurdle for fast and agile research.

- Lastly, for most organizations past research is stored as reports rather than nuggets. So adopting an atomic research repository leads to a dilemma: historical research data have to either be manually reorganised - a very time-consuming task - or disregarded.

Our decision against the atomic format doesn’t mean it’s necessary to read through all the study results to get to the point you were looking for. You can still find and jump to a single element in a study. But making colleagues access findings via the project forces them to consider where the findings come from.

Now one might argue that businesses don’t always operate within the strict boundaries of a project. You may want to combine findings from different studies to answer research questions. And you are right. We are all for triangulating data.

However, there are two important distinctions. Firstly, we believe triangulation should not be performed by stakeholders (read: anyone in the company). To keep quality high, people who are trained in research (PwDR) should be involved and ensure proper use of raw data. Secondly, it’s more efficient to triangulate data on-demand to answer specific questions. It shouldn’t be a required task every time new data is added to the repository.

Drawbacks

This approach demands a bit more effort from stakeholders to find relevant data. Not having findings pre-organized into certain topics requires to pull them together from several studies.

Want to read more? Check out our articles about what a UX research repository can do for you and how to develop the right taxonomy for your UX research repository.