User Diary Studies - An Effective Research Method for Evaluating User Behavior Long-Term

One interesting UX research method to keep in your toolbox is user diary studies. This method is beneficial if you aim to collect data over a certain period of time. It’s also a handy research method when direct observation is impossible.

In this article, you’ll learn about the basics of user diary studies as a UX research method. You'll see when it works best, and where it has its limitations. I’ll walk you through all the steps to successfully conduct a diary study along with a real-world example from a past study.

I've also included a template for user diary studies at the end.

- What Is a User Diary? 📔

- Advantages and When to Conduct Diary Studies 👍

- Limitations and Pitfalls of User Diary Studies 🙅

- How to Run Your User Diary Study from A-Z 🎯

- Step 1: Prepare the Diary Study

- Step 2: Design the Study

- Step 3: Recruit the Participants

- Step 4: Launch and Follow-up

- Step 5: End the Study and Get the Diaries Back

- Step 6: Analyze the Data

- Step 7: Follow Up with the Users

- Step 8: Sharing the Research Results

- Real-world Example: User Diary Study for the Rebuilding of an Internal Enterprise Tool 💡

- Spreadsheet Template 🖇

- Summary

What Is a User Diary? 📔

User diaries, or user diary studies, are a self-reporting research method. Research participants log their experiences, behaviors, activities, and thoughts over a certain period of time. Hence the name "diary."

Over time, researchers conduct diary research by collecting the diary entries of engaged participants. Researchers may also ask participants to take pictures or videos to better understand their environment. The diary data collected is primarily qualitative. But depending on your research goal, you can also collect some quantitative data.

Diary studies are a discovery phase research method: Used at the beginning of the user research process when you are trying to frame and understand user problems.

Researchers can also use diary studies for validation purposes. This helps when you want to make sure your design works and solves the users' problems. Diary studies are often conducted after the first phase of interviews or contextual inquiries.

I use diary studies in my projects in order to understand if content is missing from the beta version we already shipped. More on this later in the article.

Advantages and When to Conduct Diary Studies 👍

The main advantage of a diary study is the ability to collect data over time. Also known as "longitudinal information." This allows researchers to understand temporal dynamics: How user behavior and experience might change over time. It's an excellent method to collect information about habits and processes.

Additionally, this method helps to understand the events' flow and successions over time. This method also lets you capture unplanned or hard-to-plan tasks and activities. It is an excellent way to gather data about user behavior or tasks that happen sporadically.

It's also possible to learn about tasks or activities that occur at a specific time and can’t be replicated by asking research participants to do them in front of you.

For example, if you're working on a period tracking app, a user diary study can cover varying cycles over a certain period of time. Every cycle can be different and they can be very unpredictable. So observing users filling in data when their cycle starts might be hard to plan.

As a user diary study is a self-reporting method, users input the data themselves without a researcher’s help. This makes the collection of data less intrusive than other user research methods that require more direct observation or over-the-shoulder shadowing.

For example, it’s particularly suitable for situations where researchers need to collect qualitative data on matters that are more sensitive, or from populations that can't be observed directly.

In comparison to other qualitative research methods, it's also more likely to stave off biases during observation. This makes the data collection more natural in its context. And diary study participants can report influential external factors from their natural environment.

For example, during a project to monitor cranes on construction sites, crane operators used our tablet app in various different environments. Such as under bright sunlight, in dark spaces, and in very dusty environments. The results from this diary study taught us that contrast was super crucial for that app.

Limitations and Pitfalls of User Diary Studies 🙅

The main advantage of user diary studies can also be a significant limitation. This method follows users over a period of time. So if the allotted time for your research is relatively short, then conducting a diary study is likely not a suitable method for your current project.

It also requires a lot of commitment from the users. Which often results in the need for bigger incentives and bigger budgets. In other words, this is not a "quick and dirty" method. People might also forget about completing the diary study. So follow-ups and reminders are essential (more on that in the next part).

It's also important to be aware that self-reported data may not be 100% accurate and is often biased. People are not always good at reporting their own emotions, for example.

If possible, keep your journey task-oriented and factual. Don’t ask people to imagine their future. Don't ask them to remember a past event that happened a long time ago. Don't ask things like “how much would you pay to use this tool in the future?” or “what other tools did you install in the last year to accomplish that task?” A year is a long period of time.

Another limitation is missing data. It's possible that user diary entries will miss out on data that could be of interest to you because the users didn't think to report it. You can mitigate this by giving them clear and detailed instructions during a good kick-off session.

Also, keep in mind that you will gather a LOT of data through diary studies. So prepare yourself for long data analysis sessions.

Step 1: Prepare the Diary Study

Like most research methods, the first step is to prepare your study. Here’s how:

Start with your research questions/goals: What are you trying to learn or understand? What data do you want to collect? Good research is about asking the right questions, to the right people, at the right time.

You need to define a clear scope and user group: Who will you send the diary to?

Tip: Document the answers in a user research plan.

Then, decide on the trigger: When do people need to log something in the diary?

The type of trigger depends on your research questions and what you are trying to understand. As mentioned above, this can be an event, a specific interval of time, or a prompt.

For example:

"people log whenever they use a specific tool" (event trigger)

"people log every week, on Sunday afternoons" (interval of time trigger)

“people log whenever we send a prompt” - In case the stimulus is a prompt, you need to decide when you want to prompt people. And how you will prompt them.

You also need to decide how long the study will run for. You can't expect people to fill in a diary every day for six months. How much data you need depends on your study. But don't be greedy.

Do you need THAT much data? Usually, 2 weeks to 2 months is a good time frame for a typical diary study. But again, this depends on the type of study you are conducting.

Next, decide on what to capture and how: This could be in the form of text, audio, video, or photos. The kind of content that you want to capture may influence the research tool that your study participants use to collect diary entries.

In the end, go for the tool that makes the most sense for your users. Choosing a diary study tool they are comfortable with can be crucial for the success of the study.

Here are a few options:

Old school written diaries: cheap, but handwriting can be hard to read

Electronic diaries in a digital file: like a Word document, or Excel sheets. If they are supposed to add photos, PowerPoint or Keynote could do the trick. You can ask people to fill one slide per trigger.

Online survey tools: people fill the same survey, again and again, for each trigger.

Communication tools: emails, Slack, WhatsApp, etc. are great tools if you need to use prompts. Exporting data might be tricky though.

Some UX research tools offer specific diary study options.

Step 2: Design the Study

Diaries often have two parts: instructions and the actual data collection part.

Even if you have a kick-off meeting, reminding users of some information about the diary is essential. Here is a checklist of what you can put in the instructions:

- The goal of the research to help them understand the context

- When to log a diary entry (trigger)

- How long they will need to fill in the diary

- Who they can contact (and how) in case of questions, issues, etc.

- Specific instructions depending on what you want to collect

- An example of an entry

With each entry, the diary becomes a more complete collection of the data you are requesting from users.

You can have a very open format with one big, generic field where users record an entry however they want. Or, you can have a closed format with predefined, closed-ended questions.

After you’ve created your diary and your instructions (incl. prompts and questions), don't forget to pilot test it. Run a version with your colleagues, and double-check to make sure that you don't miss any typos.

Also, pilot the prompt system if you need one. For example, test the tool you will use to send emails to ask people to complete their entries. Make sure the email arrives and is readable.

Step 3: Recruit the Participants

You recruit users for user diary studies like you would for any other UX research study. But, there are a few specific details you need to be aware of when you conduct diary studies:

Diary studies require commitment over time. Make this clear when you are recruiting participants.

The higher the commitment, the higher the incentive you should provide.

You will have dropouts, so plan ahead by scheduling extra participants.

Step 4: Launch and Follow-up

You've designed a very nice diary study. Great! But, you can't just send it out to users and expect them to fill it in.

When you conduct a diary study, you should start with an onboarding session for your users. It can be a 1-on-1 session or a smaller group session. I tend to prefer 1-on-1s so that I can answer specific questions that they have.

Explain what is expected of them and how long the study will run for. Also, explain the trigger, especially if it is an event trigger. Answer all the questions they have. And more importantly, ensure that they know how to contact you if they have more follow up questions.

Go through the diary with them. If it's a digital file, make sure they can open it. If it's a survey, make sure that it works in their browser. The goal of this session is to remove every friction that could occur once they are on their own.

During the study, don't leave participants alone if you want them to stay engaged. Check-in with them and send them reminders, even if it is not a prompt-based survey. It can be a short email, or a quick call. The format is up to you.

If some people drop out, following up with them is a good way to see if you can bring them back into the study and understand why they dropped out.

Step 5: End the Study and Get the Diaries Back

Give your participants a heads up a few days before they reach the end of the study. If the tool wasn't synchronous, like a Word or Excel sheet, it's now time to collect the files. Don't forget to back them up somewhere, just in case.

And of course, thank the users for their time and explain how they can receive their incentive for participating in the study.

Step 6: Analyze the Data

I usually do a first run of "quick analysis" by reviewing the files and answers to get a basic idea of the data that was collected.

If you use a tool that lets you get the raw data in real-time, you can start a pre-analysis before the study is completed and get started on tagging the data, noticing patterns, etc. Be careful not to draw any conclusions yet, though!

How you analyze the diary's content depends on your research question and scope. Since you’ll get a lot of open content, this may take some time. I recommend doing this step with your team. I am a big fan of excel sheets for such work.

I always start by cleaning up the data. Are there any diaries that have been completed poorly? Remove them if the information quality won't bring anything to the study.

You can make use of dedicated tools for both qualitative and quantitative data analysis. Qualitative data (open content, audio transcripts, long texts, ...) can be a bit tricky to work with, but there are plenty of methods you can use to analyze it.

I find techniques like thematic analysis and rainbow sheets to be helpful research methods.

Step 7: Follow Up with the Users

Depending on the study, you'll want to debrief with your diary study participants once you have finished analyzing the data. Maybe you have some follow up questions you'd like to ask about one of the topics. Perhaps there is a specific entry you don't quite understand. You can schedule short follow-up sessions with the users if needed.

Scheduling a post study interview is also a good opportunity to thank your participant again. You can also ask for additional feedback about the diary, which can be especially helpful if you think you might run the study again. Was it too long? Too difficult? Were the questions clear? Did you have some people drop out?

Step 8: Sharing the Research Results

Following up and finishing the analysis brings you to the next step: Sharing the results with your team(s).

The format, again, depends on the data collected and the study. It can be a report. Or you could build customer journey maps, empathy maps, etc. The format is up to your specific needs.

Real-world Example: User Diary Study for the Rebuilding of an Internal Enterprise Tool 💡

As a general rule, investment banks are often a bit behind the curve when it comes to technology.

I recently worked on a project updating an internal tool for just such an organization. The platform was intended to help employees from different departments create and follow financial projects. The interface we were tasked to improve was 15 years old and required a complete rebuild!

To gain a better understanding of user behavior and how the existing tool was being used, we conducted user interviews. We collected data on their tasks and activities to ensure we migrated the right content and features.

Since we work in an agile way, we had already created pages and features that were available for users to try out in a beta version. After the interviews, we gave our early adopters access to that beta version.

We then conducted a diary study to understand the user migration and usage of our new version over the course of a month. We wanted to understand a few things:

How was the adoption going for new users?

Was there anything that stopped them from doing their daily tasks and activities with the new tool (missing content, features)?

Were there things we migrated but users couldn't find in the new tool (usability or information architecture issues)?

Did they have any improvement suggestions?

The diary study started with a one-hour kick-off session with the users. We gave them access to the new tool and observed them performing their daily tasks on the latest version.

Next, we explained the concept of the user diary. We asked them to use the new tool on a daily basis and provided them with an excel sheet to be completed over the next month.

Finally, we explained the trigger: Log an entry whenever you need to do something, but aren't able to with the new tool (and need to go back to the old one).

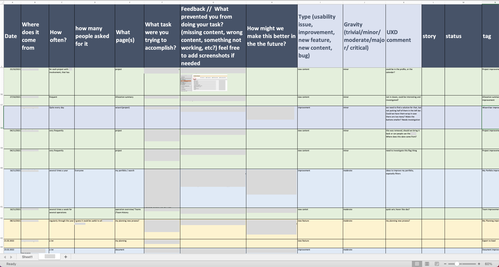

After a month (and some follow-ups), we collected the diaries and merged them into one extensive document. In this document, we added a few extra columns to help us analyze the data:

Type (usability issue, improvement, new feature, new content, bug): Color-coded for faster identification within the file.

Gravity (trivial/minor/moderate/major/critical): Helpful for prioritization.

UXD comment: A column for extra information, like how we could improve it, or "have a follow-up interview with a user for this topic."

Story: To link to the user story.

Status: To show the status of the story.

Tag: The main topic of the entry. This was used for quantitative purposes to see which main issues we needed to tackle in the subsequent releases.

Here’s what that looked like for our project on internal tool migration:

Once our data was combined into a single spreadsheet, we went through each diary entry and began our analysis. We discussed each task that users could not complete using the new version of the tool, determined the gravity of the task, and if/how we would incorporate this into the future tool.

Our diary entries were very task-oriented. For example, people reported specific tasks they were trying to accomplish with the search and said precisely who/what and how they went about searching for this information. This helped us gather feedback and plan improvements.

This also allowed us to identify usability issues for features or content that might not have been clear in the new tool. For example, if a user logged content as missing, but we had already migrated it, this could be considered an issue.

All that data also helped with training and building our FAQ, which our enterprise users expected as part of change management.

Conclusion

As a result of conducting the user diary study, we were able to ensure that the new tool offered all of the original functionalities while incorporating some desperately needed updates.

The users played an integral role in the success of the new tool by allowing us to see what components were essential for them to do their jobs effectively. It also helped us evaluate what was missing by giving us a sneak peek into their daily tasks.

Spreadsheet Template 🖇

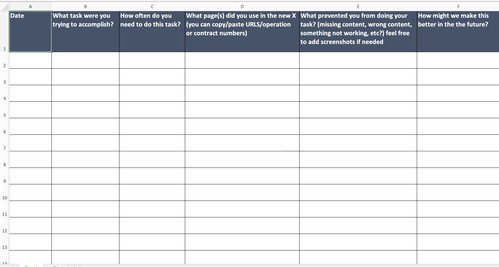

If you choose to go with an excel sheet, you can use my template here:

The first sheet is the instruction sheet. Input all the instructions for your users: When to log, how much information to enter, contact information, etc.

Then ask your users to log entries into the second sheet, the “Log here”-sheet. This sheet is for data collection. You need to adapt the columns to your specific needs.

In the next step, you can build a consolidated sheet with all the data you collected from all the diaries.

Summary

User diary studies are a self-reporting research method: users fill in diary entries on their own.

Diaries are a great tool for collecting data over time. They can be especially helpful in situations where you can’t observe participants directly, for unplanned tasks, and for tasks that can’t be replicated.

It requires a time commitment from the participants and the data might not always be perfectly collected.

There are 3 types of triggers for a diary: event, prompt, and interval.

Choose the trigger and format for your diary study upfront.

When recruiting participants, make them aware of the amount of time it'll take.

Schedule onboarding sessions and follow-ups if you want the method to work.

You can collect both quantitative and qualitative data.

Schedule follow-up sessions with participants to discuss entries, get more information, and thank them.